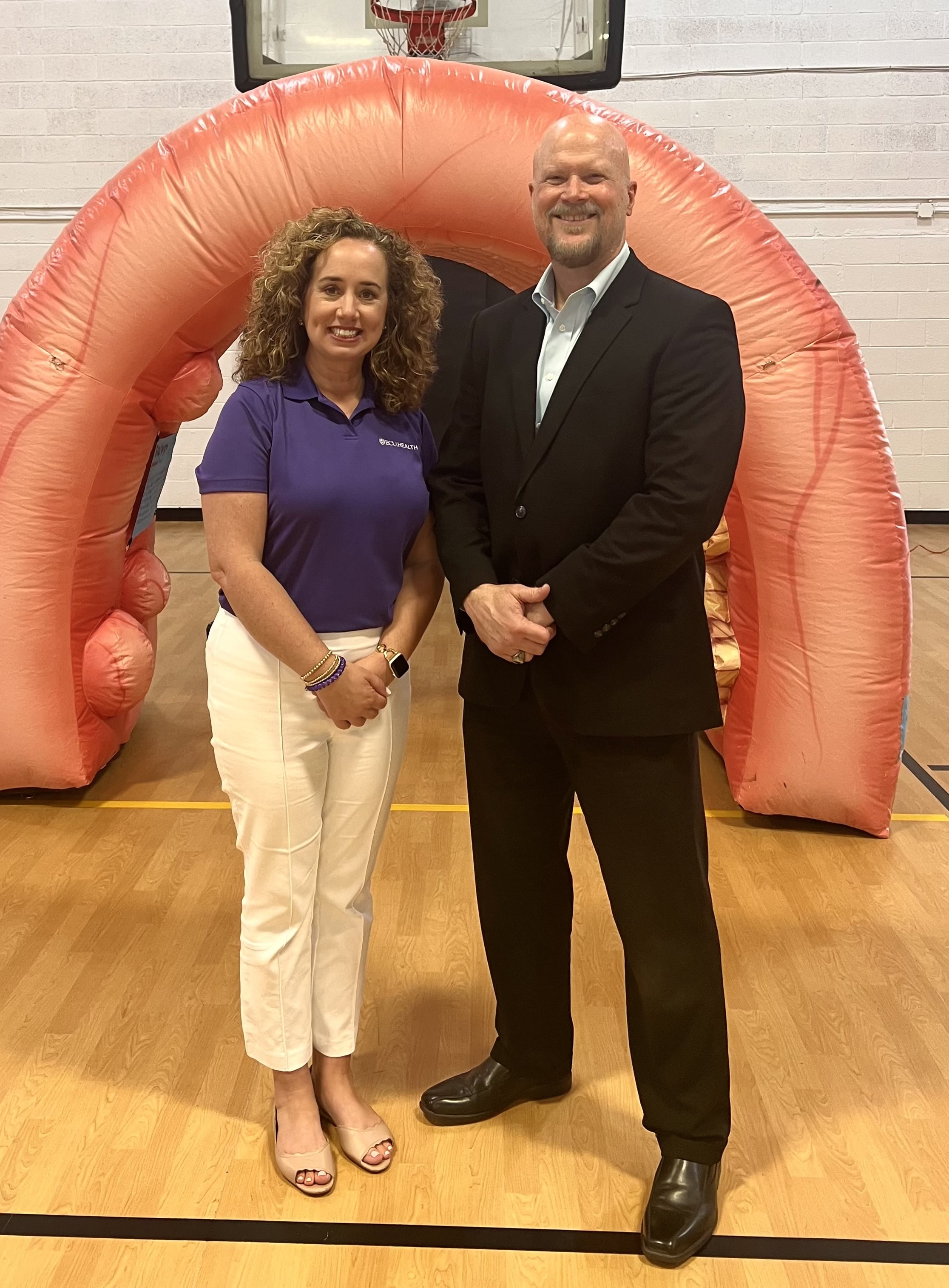

ECU Health leaders joined Care4Carolina, a coalition of organizations across North Carolina working together with the goal of bringing affordable health care to North Carolinians, for a Medicaid expansion event March 18. Partners from Pitt County Community College, Pitt County Social Services, and local representatives and leaders teamed up to bring Medicaid registration resources to local community members.

Health care access and delivery in rural areas often differ significantly from their urban counterparts, and this reality is apparent in eastern North Carolina. Every year, approximately 140,000 individuals turn to ECU Health Medical Center for emergency department services alone. Historically, uninsured patients have sought primary care in emergency departments due to their inability to afford preventive care. Medicaid expansion holds promise in bridging the gap, connecting people in the East and beyond with essential preventive and primary care services, ensuring their well-being is prioritized before the need for high-acuity care.

With 40 percent of Americans residing in rural areas, ECU Health plays a crucial role in providing care to some of the region’s most medically vulnerable individuals through its network of nine hospitals and 185 primary and specialty care clinics across eastern North Carolina.

Brian Floyd, chief operating officer of ECU Health, said partnerships are among the most important elements in delivering health care to the community.

“ECU Health has been a strong proponent of Medicaid expansion for six years,” Floyd said. “It is a necessary component to solve the complexities of rural health care delivery. Medicaid expansion allows us to have the resources to continue to invest in our communities and help us render high-quality care to those most in need. We finally have reached the point where historic access to Medicaid is available, and it becomes incumbent upon all of us to encourage everyone eligible to sign up to transform their lives. I want to thank the General Assembly for taking a bold step to move us forward in taking care of the people in our communities.”

Learn more about Brian Floyd and his role at ECU Health on his Thought Leadership page.

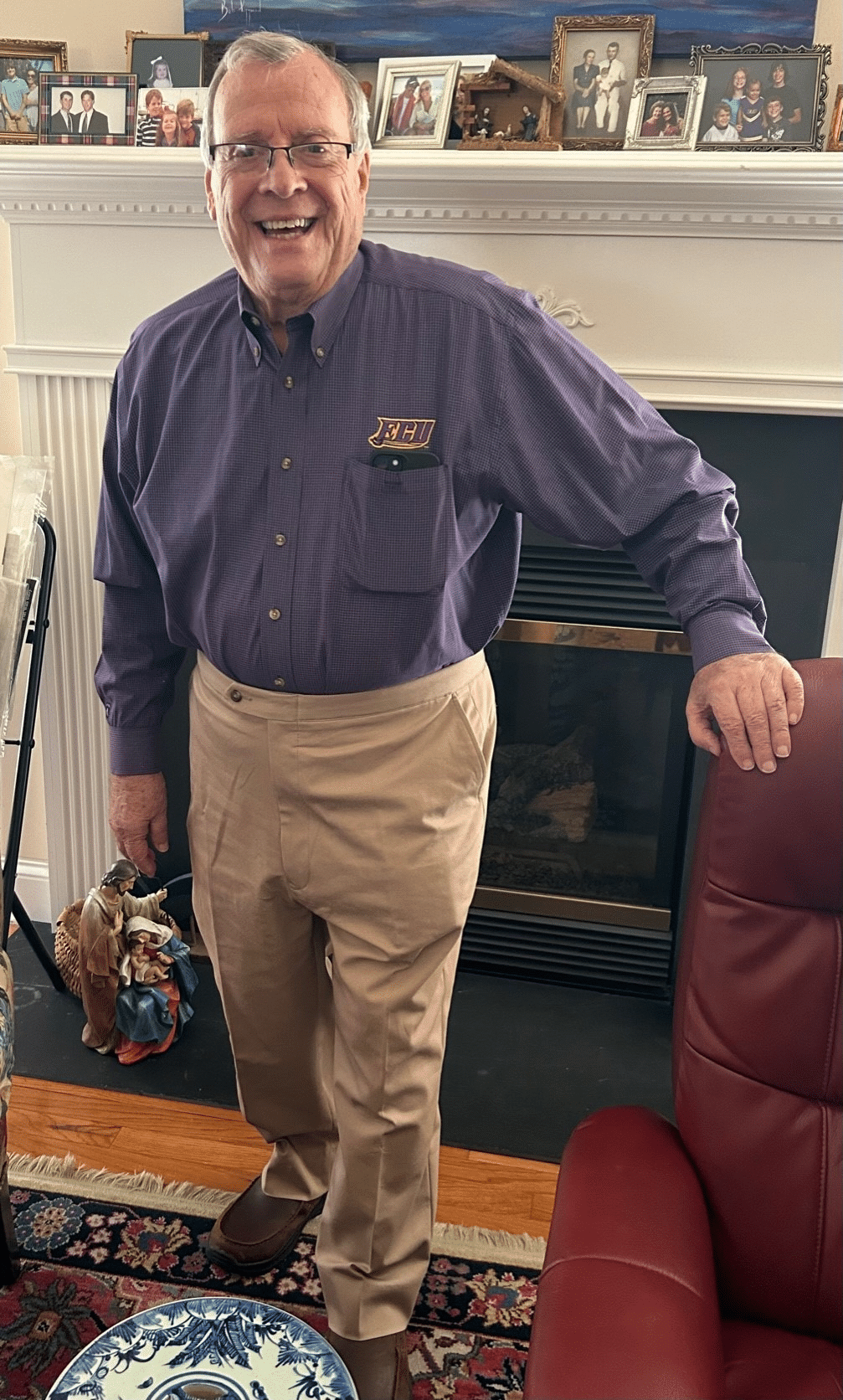

John Core had never heard of pulmonary rehabilitation until he needed it.

“I went to urgent care with what I thought was a bad cold,” Core said. “But my heart was racing so they sent me to the hospital.”

Once in the ECU Health Medical Center emergency department, Core said they were unable to get his 144 beat-per-minute heart rate down with medications; the next step was to perform an electrical cardioversion, which is where the heart is shocked to restore a normal rhythm.

“I wound up in the ICU and stayed in the hospital for two weeks,” Core said. “When I got out, I had trouble breathing and had to be on oxygen, which I hated.”

After a six-week recovery, during which time Core said he could barely walk, his doctor recommended he try pulmonary rehabilitation.

“I was encouraged that my doctor thought I was strong enough to go,” Core said. Upon arriving, Core immediately felt comfortable in the rehab setting. “They were supportive and guiding. They were wonderfully attentive, and their sense of humor and generosity with their time made it the best experience I’ve ever had in health care.”

Pulmonary Rehabilitation helps reduce and control breathing difficulties and other symptoms of lung disease, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pulmonary hypertension. ECU Health’s Pulmonary Rehabilitation team strives to help patients achieve their highest level of independence and physical ability.

Initially, Core could only walk one lap around the therapy track with the assistance of oxygen before needing a rest; but week by week, he increased his distance. He was impressed by the rehab team’s consistent regimen and organization.

“You had a set routine every visit: sign a form, get weighed, take your blood pressure and then start your program.” The planning and tracked improvement helped drive him to want to go to therapy his prescribed three times every week. “They made me like exercise, when I hated exercise before. I used to think exercise was a waste of heartbeats.”

Core was also impressed by the pulmonary rehab team’s rigorous standards and attention to detail.

“At first, I couldn’t go to the grocery store because I couldn’t walk the aisles,” Core said. “Then I got the idea that I could lean on the cart and put my oxygen tank in the cart. I was so proud of myself.”

The next day, Core said he told his rehab therapist what he’d done.

“She said, ‘That’s not good enough.’ At first that hurt my feelings, but she was right. It pushed me to walk longer and harder.” Any time Core showed signs of fatigue, he was made to rest so they could monitor his oxygen saturation, which should be above 90%. “When they saw I was throwing PVCs [premature ventricular contractions] during my walk, they stopped therapy until I was cleared by my cardiologist,” Core said.

PVCs are extra, abnormal heartbeats that disrupt a normal heart rhythm.

One day, Core asked the rehab team if he could try walking two laps without oxygen.

“They agreed but monitored me very closely. After my first lap, I was at 90-91% oxygen, thank the Lord.”

From there, Core worked his way up to 11 laps just prior to graduation. Now, Core said he is feeling better than he did before his stay in the hospital.

“After graduating from pulmonary rehab, I joined the ECU Health Wellness Center, and I really enjoy swimming. I’ve lost over 30 pounds, I exercise regularly and I’m overall trying to improve how I live my life. I like where I’m at,” he said.

Core works at East Carolina University as a special assistant to the dean in the School of Dental Medicine, and he enjoys spending time with his wife of 32 years, his children and grandchildren. He’s also looking forward to a great grandchild on the way. This spring, he and his wife have plans to resume travel to visit his daughter and son-in-law in Charleston, South Carolina. Taking a trip like that wasn’t feasible prior to his experience with the amazing Pulmonary Rehab team.

“I had trouble walking; I couldn’t even walk a quarter of a mile,” Core said. “Pulmonary rehab helped me back. They know what they’re doing, and you can depend on them. To know that people care for you – it makes a difference. I can’t tell you how good they make you feel if you let them.”

Greenville, N.C. – ECU Health Medical Center has been nationally recognized in Becker’s Hospital Review as the top hospital in the country for patient experience, according to a new ranking from PEP Health. PEP Health analyzed more than 30 million online patient reviews from hospitals across the country in 2023.

According to Becker’s, PEP Health extracts behavioral insights data from patient comments shared on multiple social media and review platforms. Hospitals with at least 300 staffed beds and at least 250 patient experience comments were assessed across seven domains: fast access, effective treatment, emotional support, communication & involvement, attention to physical and environmental needs, continuity of care, and billing and administration.

“At ECU Health, creating positive patient and team member experiences is at the heart of who we are as a mission-driven organization,” said Dr. Julie Kennedy Oehlert, chief experience officer, ECU Health. “Our continuous journey toward excellence in patient care is informed by the perspectives of our patients and driven by the hearts of our team members. Our patients know that ECU Health team members are here to care for them with compassion and respect. It is gratifying to know our intentional focus on creating safe, healing environments is affirmed by the feedback of those we are honored to serve. We are incredibly grateful to our patients for their honest review of the care we provide.”

ECU Health’s commitment to creating positive patient experiences can be seen across the health system. The Outer Banks Hospital achieved 5-star status in overall patient experience in 2023 and ECU Health Bertie Hospital met requirements for 5-star status as well from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) utilizes these star ratings to summarize the patient experience, which is one aspect of hospital quality. The ratings are based on surveys that patients fill out after their inpatient stay and are designed to help patients choose excellence in health care. The HCAHPS survey captures the patient’s experience of communication with doctors and nurses, responsiveness of hospital staff, communication about medicines, cleanliness and quietness of the hospital, discharge information, transition to post-hospital care and overall rating of the hospital.

ECU Health’s providers also play an important role in supporting excellence in patient experiences. In the clinic setting, 99% of ECU Health providers are rated by their patients as 4.0 or higher out of 5 stars, with 96% of those providers being 4.5 stars or higher, according to Press Ganey LLC. ECU Health’s providers’ overall ranking as a medical group for excellence in care is 4.7 out of 5 stars based on patient reviews from Healthgrades, Google, WebMD, Wellness, Vitals and more.

“I am proud of the doctors, nurses and all team members who work tirelessly to deliver highly-reliable, human-centered care to eastern North Carolina,” said Brian Floyd, chief operating officer, ECU Health. “The experiences we create within our health care settings can leave lasting impressions on those we serve. I am fortunate to witness ECU Health team members in action every single day, and their role in compassionately caring for our community members – often during their most difficult moments – is central to our mission of improving the health and well-being of eastern North Carolina.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, colorectal cancer is the fourth most common cancer, apart from some kinds of skin cancer.

While colorectal cancer is common, early detection and prevention can be lifesaving. Of those ages 50 to 75, only about 7 out of 10 adults in the United States are up to date with their colorectal cancer screenings. Screenings can be done in a variety of ways, some of which include colonoscopies and fecal testing. When cancer is detected through preventative screenings, treatments can begin earlier to increase the chance for positive outcomes.

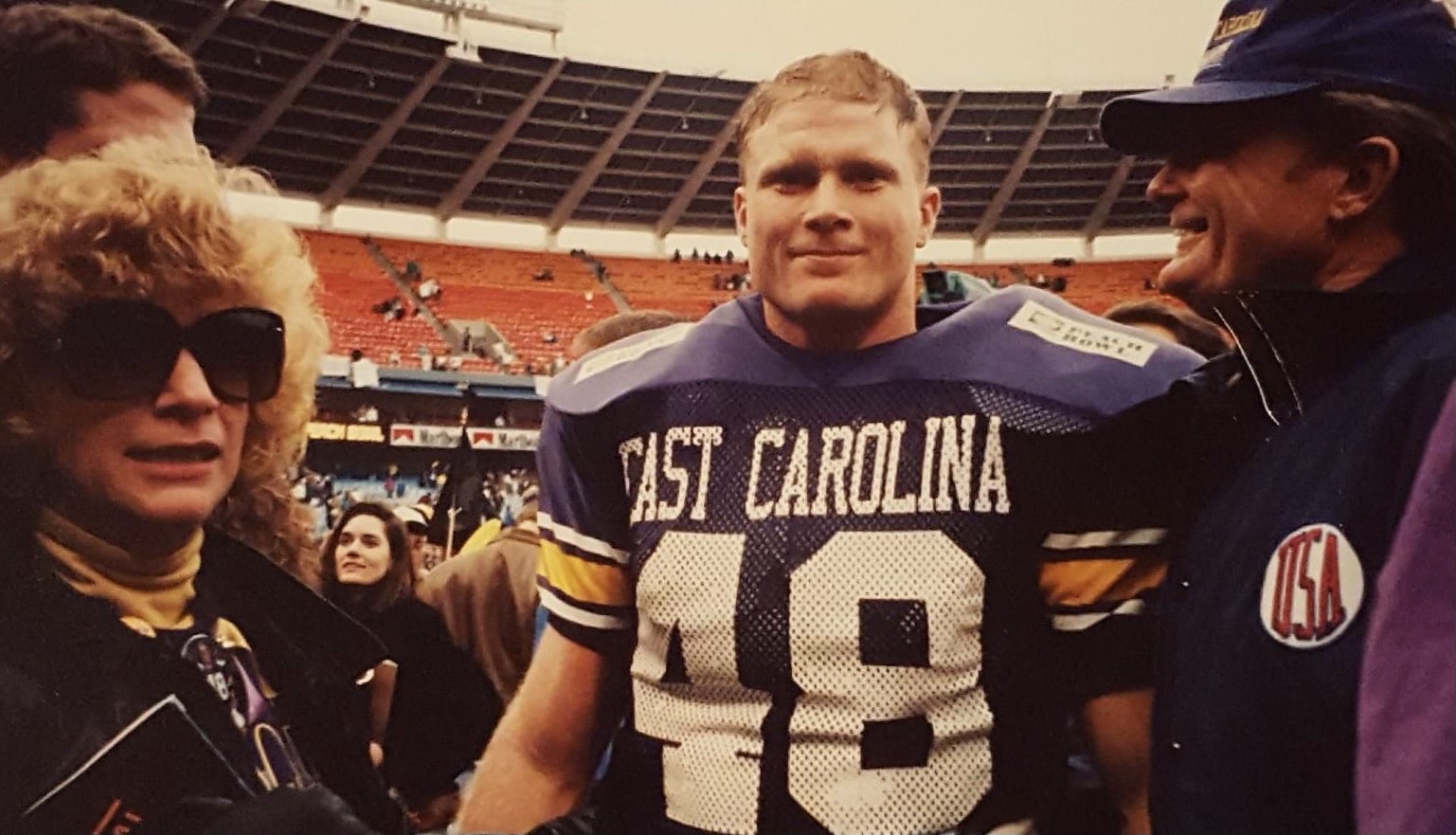

No one knows the importance of screenings more so than Stephen Braddy.

Braddy grew up in eastern North Carolina and played various high school sports before going on to East Carolina University to play football as a linebacker, even playing in the 1992 season that led the Pirates to the Peach Bowl. Now, Braddy is retired and works at Washington Montessori School. He also spends time advocating for the importance of colon cancer screenings.

This cause is important to him because in 2022, after encouragement from his family and friends, he scheduled a colonoscopy at ECU Health which led his doctors to discover a mass in his colon.

“I woke up from the procedure and the doctor comes in with this look on his face and says we’ve got some issues,” says Braddy. “We couldn’t finish the colonoscopy because there was a tumor the size of an egg in the way. I was immediately sent for blood work and scans.”

Braddy was quickly scheduled for surgery on July 12, 2022. During the surgery, doctors removed part of his colon, the mass and 19 lymph nodes, as well as did a colon resection. Following the surgery, he went through four sessions of IV chemotherapy with chemotherapy medication in between.

As a former college football player, Braddy has always been an active person, and he wasn’t going to let treatment keep him from staying active.

“I wanted to show cancer up and beat it,” he says. “Right after my first chemo treatment, I got home and went on a run. I continued to work out through all the sessions.”

In addition to staying active, Braddy also fasted for 68-72 hours around each chemotherapy session. He credits both fasting and staying active as helpful in controlling his nausea and fatigue after treatment.

Since his diagnosis, Braddy has become passionate about talking to others about the importance of colorectal cancer screenings.

“If I could rewind things, I would have no hesitation to get a colonoscopy done so much sooner. The colonoscopy procedure is easy and well-worth the effort it takes to get one. A lot of people, including me, think ‘this will never happen to them.’ Screening could have prevented me from surgery, chemo and bills,” he says.

Regular screenings for colorectal cancer are recommended to begin at age 45. If you’re eligible for a screening and do not have one scheduled, take time during Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month in March to talk to your primary care provider, obstetrician-gynecologist or gastroenterologist about scheduling an appointment.

Now, Braddy is cancer-free, and continues to stay on top of his appointments to take preventative measures to stay healthy.

“If there’s one thing I would say to people it would be that just because you feel good doesn’t mean something might not be wrong,” Braddy said. “Colon cancer is very treatable if caught early. If not for yourself, schedule a screening for your family and loved ones.”

Learn more about screening locations and scheduling information on our Reminder page.

Dr. Niti Singh Armistead, the chief quality officer and chief clinical officer at ECU Health in Greenville, keeps making the right career choices.

In college at George Mason University, she switched her major from engineering to physics and pre-medicine after she discovered that there were loans available to pay for medical school. “I appreciate what programmers do every day, but I realized that my own joy was working in the medical field,” she says.

After graduating from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, she specialized in anesthesiology, thinking her physics background would be helpful. She switched to internal medicine because she found the long-term relationships with patients more enduring and satisfying.

Now, at ECU Health, she’s focused on acute care and still sees patients on a regular basis. She took on administrative roles in 2018 and 2019 before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, successfully helping steer the healthcare system during a challenging time.

“None of us knew what we were in for,” says Armistead. “For me, it all just kind of came together. How do you support an already underserved population? How do you rise to the occasion as the only healthcare system east of I-95 with an academic arm to do it all, to build the infrastructure for the testing and to educate the community? Those were the kind of interventions I got to lead.”

Read the full story in Business North Carolina.

ECU’s clinical laboratory science students — who after graduation run the nation’s medical labs in hospitals, for public health offices and in the pharmaceutical and biotech industry — got a huge boost recently with the acquisition of a new device that automates the process for identifying blood types.

Funding for the new system, some $6,600, came in part from the American Society for Clinical Pathology and the ECU Medical and Health Science Foundation’s CLS Priority fund.

The instrument, known as the Ortho Clinical Diagnostics workstation, replaces a laborious process of mixing blood samples with reagents by hand to allow laboratory professionals to quickly and accurately establish blood types and identify donated blood that can be safely transfused to a recipient.

Traditional blood analysis methods, which ECU’s Department of Clinical Laboratory Science chair Dr. Guyla Evans and her faculty peers still teach their students, involves mixing drops of blood with antibodies that register specific blood types. The process also registers Rh factor, proteins on the surface of some people’s blood cells that affect who can receive blood donations from whom.

Using the established test tube method is a time and attention intensive process.

“It can be kind of hard to teach students how to read the tubes because it’s subjective. You have to read the tubes right away, and there are a lot of steps,” said Michael Foster, a senior from Roanoke Rapids, who already works in the blood bank at ECU Health Medical Center in Greenville.

Using test tubes to identify blood samples is a tricky business: laboratory personnel must identify cell reactions by eye and they have a limited time to observe and interpret the results.

“The name of the game in blood banking is accuracy, but it’s also speed. You want to get it in the centrifuge and as soon as it’s ready to come out of the incubator and get it going,” Evans said.

The new system uses a cartridge, which requires less blood in the sampling process and has the advantage of leaving the sample readable by technicians for up to 24 hours. This allows laboratorians to double check their work or have a peer review their results.

An added benefit for the cartridge system is baked-in surety of the testing chemicals.

“You don’t have to worry about adding the wrong reagents because the cards are color-coded and the reagents are already added in,” Foster said.

Each cartridge may cost up to $25, which isn’t cheap, but Evans and Lorie Schwartz, a research technician and CLS instructor, both agree that the new system is at least as cost effective as traditional testing methods due to labor costs and the intangible benefit of assurance that the results are valid.

The new system is less mentally taxing for the medical laboratory scientist, Evans explained.

“In the blood bank, everything has to be carefully documented. Nothing is ever assumed or taken for granted—blood bankers trust no one, they believe no one,” Evans said. “If I’m going to do a cross match for two units, and the antibody screen and the blood typing, that’s 12 to 15 tubes that I have to label every time. It’s a lot faster to label one card or a couple of cards, depending on what testing you’re doing.”

The CLS department received the equipment in December, just a bit too late for the current class of students, including Foster, who will graduate in May. The seven graduating students were able to train on the gel microcolumn system during clinical rotations with ECU Health and Nash UNC Health, where they got hands-on experience.

Evans said the COVID-19 pandemic made teaching blood banking techniques very difficult because, while theory is crucial to understanding lab work, getting hands-on training is critical for learning.

Students who learned during the pandemic were dropped into the deep end during clinical rotations in working labs and had to put theory into practice, both with traditional test tube methods and the gel cartridge system.

“During clinicals, we went through quite a number of cards trying to figure out what antibodies were present in the blood because they would give us unknown samples and we would spend the entire eight hours trying to figure out what the sample was,” said Bryce Glover, a senior from Fayetteville. “If we went down the wrong path, that was one card wasted.”

Because they are eligible to work in clinical labs once their clinical rotations were completed, Foster, Glover and the other members of their cohort already have jobs in area labs.

“ECU Health and ECU’s commitment to incorporating the latest technologies into both health care delivery and hands-on training for our future workforce not only benefits students during their academic journey but also equips them with valuable skills that are highly sought after in the health care industry,” said Carolyn Merritt, ECU Health lab scientist.

“Keeping students up to date on the latest technologies, such as gel testing, is crucial for optimizing their limited time during clinical rotations. Our goal is to help prepare the next generation of high-quality health care professionals, and hands-on experience with innovative technology ensures our students are well equipped to provide important services once they enter the workforce,” Merritt said.

The advances in high tech equipment, combined with severe staffing shortages, have exacerbated what Evans sees a worrying trend — laboratory professionals aren’t seen on the hospital floors or interacting with nursing staff.

Being squirreled away in a windowless lab the majority of the workday means that medical laboratory scientists and technicians are often disconnected from their peers. Evans counsels her students to be part of the hospital and medical communities they will eventually be part of.

“They must make an effort to be seen as part of the hospital team because they usually aren’t seen,” Evans said.

While medical laboratory scientists might not be as visible as other members of the health care continuum, their role in diagnosing and treating patients can’t be overstated. With an expected need of nearly 17,000 more medical lab scientists nationwide by 2032, the critical skill set that Pirate graduates bring to hospitals and clinics is invaluable.

“When our students get into the clinical system, that’s when they really see the workflow and that last piece of their education comes together,” Evans said. “We’ve been really fortunate that our clinical sites, even though they know they’re dealing with personnel shortages, are taking students on which is extra work they don’t get compensated for. They’re doing it because they know it’s important and that is invaluable.”

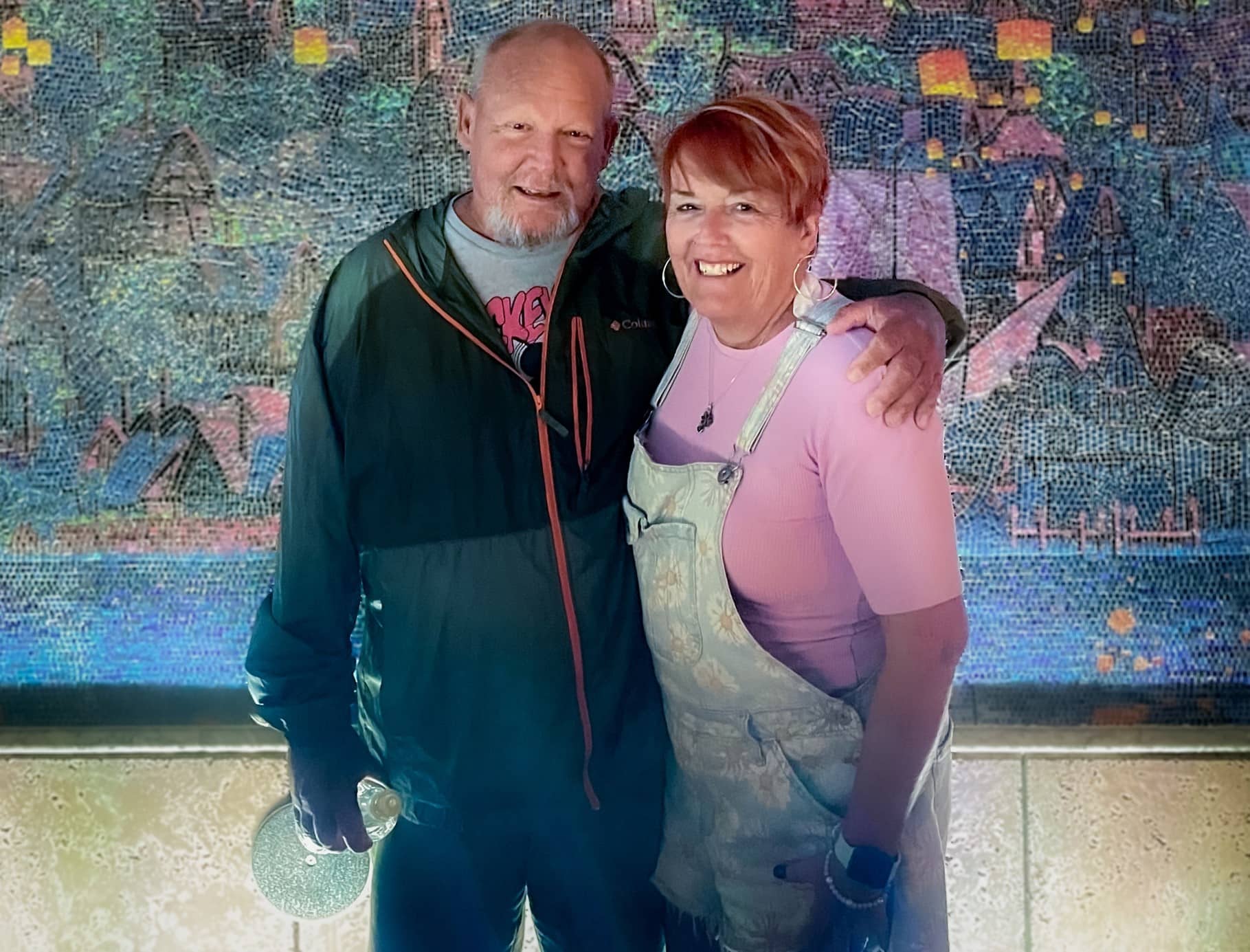

Sharon and Steve McNally of New Bern have been married for more than 40 years. Now, Steve carries a little piece of his wife Sharon with him everywhere he goes.

Steve is diabetic and in 2015, he went through his first round of transplants at a hospital in their then-home state of Pennsylvania.

“It was supposed to have been a kidney and pancreas at the same time,” Steve said. “When they got me on the operating table, the pancreas wasn’t viable. So they said, ‘We’re going to do the kidney alone and we’ll get you a pancreas.’ What happened then was the hospital eventually became decertified and couldn’t do pancreas transplants anymore.”

Then, they joined the transplant list with a health system in Maryland and Steve received a pancreas transplant 30 days later. In the meantime, the new kidney had been damaged due to the lack of a functioning pancreas, but Steve said it was largely working fine until mid-2023. By that time, the McNallys had moved from Pennsylvania down to New Bern.

With Steve’s kidney function worsening, there was little time to spare. He could join another transplant list that may take eight to 10 years to find a donor, start dialysis or personally find a match to donate a kidney.

Sharon said she knew she had to step up for her husband and get tested to see if she could be a match.

“It wasn’t really hard for me because a lot of people say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re so amazing’ or so this and that but I don’t really feel that way,” Sharon said. “I feel like we’ve been married 40 plus years. We have grandkids and kids together and how could you watch someone get more and more ill and not do something if you can? So I didn’t really think about it.”

Testing started for the two in June and preparation began right away. They found out in October they were a match and an ECU Health team performed the transplant on Nov. 7.

“I’m glad that this was something I could do,” Sharon said. “There’s a lot of people that probably couldn’t have, even if they wanted to.”

For Sharon’s part, she went home the next day while Steve stayed a couple extra days for monitoring before heading home. While they each needed some help early on after coming home, they were both happy to support each other, as they’ve been doing for more than four decades.

Dr. Margaret Romine, transplant surgeon at ECU Health, and Dr. David Leeser performed the transplant along with other members of the ECU Health transplant team. She said she was most proud that the team could take on a case like the McNallys, especially given Steve had been through a kidney and pancreas transplant previously.

“They had already been through a lot before even coming to us but they had such great attitudes and were great patients to care for,” Dr. Romine said. “We have such a great team and that really sets us apart from other programs. It’s not just about what the surgeon thinks – the nephrologists play a huge role. Our coordinators, nurses, pharmacists, social workers all play a huge role. We can’t do what we do without the entire team. Whenever we make a big decision to take on a patient like him, it’s done as a team.”

Steve and Sharon both said they were happy with their experience at ECU Health and shared appreciation for the care team that helped guide them through the process and into recovery.

Now, they are looking forward to a spring working outdoors, something they both love but missed out on last year.

Sharon said if she could share one message, it would be on the importance of organ donation.

“Organ donation is just such a wonderful thing. I mean, three different times it saved my husband,” Sharon said. “You know, a lot of people don’t want to do something like that even after they’re gone because it just it seems weird to them. But honestly, I think it’s a wonderful thing.”

NAGS HEAD — About a decade ago, the Outer Banks community suffered higher cancer mortality rates than the state and nation. Not only has that trend reversed, but now for the first time, local cancer patients can receive all their services under one roof.

Over 275 people attended the ribbon-cutting and open house on Jan. 24 for the Carol S. and Edward D. Cowell, Jr. Cancer Center. Located at 4927 S. Croatan Highway in Nags Head, it opens its doors to patients on Jan. 29.

“In 2012, Outer Banks Health didn’t have a cancer services program at all, and we were trailing the state and we were trailing the nation when it came to cancer mortality for all cancers…and we wanted to change that dynamic,” Ronnie Sloan, president of Outer Banks Health, said during brief event remarks.

The Outer Banks’ cancer mortality rate was about 6% and 7% higher than the nation and the state, respectively, Sloan said in an interview at the event.

Now, local cancer mortality rates are 6-7% lower than the state and country. The 5-year mortality for breast cancer rate dropped 50% in recent years. Even as cancer mortality rates have steadily declined across the country, “we’ve outpaced that,” Sloan said.

Carol Cowell cut the ribbon at Wednesday’s event. She made the namesake donation to the Carol S. and Edward D. Cowell, Jr. Cancer Center in Nags Head in honor of her late husband and in appreciation of the local community.

Originally from Brooklyn, New York, Cowell said in an interview that she is a cancer survivor who received treatment in Elizabeth City in 2005. The Outer Banks didn’t offer cancer services then, but she was greatly impressed by “the community sense that you got” from local health care professionals and from the community at large.

Fundraising for the center was similarly a community effort.

“This has been just an amazing journey,” Tess Judge said during her event remarks. Judge is chair of the board of directors for Outer Banks Health and co-chaired the fundraising team with Cindy Thornsvard.

Judge said she lost her mother and a son-in-law to cancer, and her daughter-in-law is struggling with it now, “so cancer services and the wonderful team we have here is just so special not only to me but to many.”

Fundraising for the center began during COVID, and their original goal of $4 million was bumped up to $6 million as the costs of building supplies soared.

According to Sloan, nearly $6.5 million has been raised for the center.

“We did that because of all of you, and the tremendous support this community has given to this cancer center,” Judge said.

Stephanie Anderson, a community member who had lost people to cancer, hiked the entire Appalachian Trail last year and raised about $10,000 for the center in the process, said Jennifer Schwartzenberg, director of community outreach and development for Outer Banks Health.

The journey to the center

Outer Banks Health hired its first director of cancer services in 2012, said Sloan, who came aboard in mid-2011.

“In 2013, the board of trustees made a fantastic decision,” Sloan said during his public remarks. They chose to purchase the radiation therapy center that was closing about two miles north of the hospital.

“We didn’t want our community to have to drive two hours each way” for treatment, he said.

Dr. Charles Shelton, a radiation oncologist, began working at Outer Banks Health — then called The Outer Banks Hospital — in 2014, and he leads the cancer services team, Wendy Kelly, marketing director for Outer Banks Health, said in an email.

Shelton set a goal of creating and maintaining an accredited cancer program to reduce the high cancer mortality rate among residents of Dare and Currituck counties, Kelly said.

“It’s been a dream of this organization since 2015 to build a facility that would allow patients to receive the highest-quality, compassionate cancer care all under one roof right here on the Outer Banks,” Kelly said.

Supported by its two partners, ECU Health and Chesapeake Regional Healthcare, along with the generosity of the local community, “that dream is now a reality,” she said.

In 2016, the Commission on Cancer of The American College of Surgeons granted a “Three-Year Accreditation with a Commendation” to The Outer Banks Hospital, which the facility has “proudly maintained” since that time, according to Kelly.

“Additionally, we are one of only eight critical access hospitals in the nation with this accreditation, and the only one nationally to have an accredited breast care program,” she added.

Outer Banks Health is one of 20 critical access hospitals in North Carolina, which have 25 beds or fewer and receive cost-based reimbursement, according to the North Carolina Division of Health and Human Services website.

“Outer Banks Health is an approved Medicare and Medicaid provider and participates with most commercial insurance companies,” Kelly said.

Sloan said that the new “comprehensive center” allows them to offer the “best care possible.”

The entire cancer team can quickly make decisions about patients in consult with one another as “concerns pop up,” and having the dedicated center eliminates the need for patients to go from the first to second floor of the hospital for care, then across the busy bypass for radiation treatment, he said.

Kelly expressed gratitude for all the community support of the center, which included the over 275 people who attended the event on Wednesday.

In addition to Shelton, the cancer services team also includes a director, three radiation therapists, a radiation nurse, a genetics extender, a physicist, a dosimetrist, a licensed practical nurse, 11 registered nurses, a nurse navigator, a financial navigator, a lay navigator, a social worker, a practice manager and three front desk monitors, according to Kelly.

“Our search continues for a permanent medical oncologist, and in the interim Dr. Michael Spiritos, formerly of Duke Health, has agreed to serve in that capacity,” Kelly said in her email. “Additionally, Dr. John Barton serves as a medical oncologist at the center.”

“Congratulations Outer Banks Health on this much-needed and impressive expansion,” Robert DeFazio, chairman of the board of directors for the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce, said during his event remarks.

Frostbite isn’t the only concern with the frigid temperatures expected in eastern North Carolina this weekend.

“You can’t smell it. You can’t see it. You can’t taste it,” said ECU Health Chief for the Division of Medical Toxicology Dr. Jason Hack

Dr. Hack said carbon monoxide poisoning can sicken people when their furnaces malfunction or they use other means to heat their homes.

He said that includes, “HVAC, our heaters in our home. Portable heaters, propane portable heaters that some people might bring in, or if they lose their electricity because of an ice storm or something along those lines, they might want to bring in a generator out of the storm or close to the home.”

Dr. Hack also said people should never sit in a running car to escape the cold if the heat is out at their home.

“Some people would tend to sit in their car and turn on turn on their vehicle while it’s still in their attached garage,” he said, “Even with the door open, these can be sources of enough carbon monoxide to injure or even, unfortunately, kill people within the home itself.”

It’s not a good idea, but a dangerous one, to use the gas stove in your kitchen to warm up the house. Dr. Hack said, “It could be producing low levels of carbon monoxide that might accumulate.”

And the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning can be non-specific.

“It can look like a lot of other things,” he said, “Such as weakness or dizziness. Some people complain of some shortness of breath. Headache is one of the most common presenting symptoms of carbon monoxide. Confusion. Some people actually complain of chest pain or palpitations and fainting.”

Dr. Hack said the best defense is a working carbon monoxide detector in every bedroom and living space in the house; he recommends that people to make sure the batteries are fresh and they’re working properly before the cold air arrives this weekend.

According to the National Institutes of Health, about 1,200 people die in the U.S. from accidental CO poisoning annually and more than 100,000 people visit the emergency department each year.

Greenville, N.C. – East Carolina University and ECU Health are launching an initiative to increase the number of adult gerontology acute care nurse practitioners serving as advanced practice health care professionals in ECU Health’s critical care settings. This effort builds on the collective commitment of both organization to solve the rural health challenges in the region as well as the state.

The effort – conceived by nursing and education leaders from ECU’s College of Nursing and ECU Health – will benefit both the university and the health system, said Dr. Bim Akintade, the dean of ECU’s College of Nursing. An investment of nearly $1.5 million over five years from ECU Health will increase the College of Nursing’s capacity to graduate trained and qualified nurses who can meet the growing need for acute care practitioners to treat the hospital’s sickest patients.

“ECU Health is proud of its close relationship with ECU and the College of Nursing, particularly as it pertains to our efforts to adapt to the national health care workforce shortage,” said Dr. Daphne Brewington, ECU Health’s vice president of nursing. “Our success as an academic health system is predicated on our ability to leverage clinical and academic excellence in order to ensure we can provide high quality health care for the residents of eastern North Carolina.”

Nationally, the aging population is growing, accompanied by the shortage of health care workers. This collaboration not only strengthens the health care workforce in eastern North Carolina but also contributes to improved health outcomes and increased accessibility to specialized care for older adults in the communities of eastern North Carolina.

Through this effort, ECU Health is helping fund the development of a new Adult Gerontology Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Post Graduate Certificate, which will train current nurse practitioners to treat acute care adult patients. The investment also provides funding for a program director who teaches and an additional part-time faculty member as well as administrative support and operational costs.

The program will reserve six enrollments per enrollment cycle for current ECU Health employees, highlighting the importance of providing specialized training that benefits the region.

“Our plan is to take the next few months to work with our partners at ECU Health and find clinical placement sites in critical care environments for ECU Health employees who enroll in the program,” Akintade said. “They need nurses, and training nurses is our business and passion. This collaboration is a win-win and makes complete sense for the University, the Heath System, the region, and the state.

Clinical placements for students employed by ECU Health will take place at ECU Health facilities, which will help to alleviate a major sticking point for training advance practice nurses – finding clinical placements for students in training. It also has the potential to create pathways for those in the program to experience acute care at both ECU Health Medical Center and in ECU Health’s regional community hospitals.

The initiative isn’t limited to the current arrangement and both ECU and ECU Health continue to explore ways to leverage this effort to design innovative solutions that benefit the people of eastern North Carolina.

“Eastern North Carolina depends on institutions like ECU Health and ECU to collaborate on innovative solutions that drive us towards our mission of improving the health and well-being of the region,” said Dr. Trish Baise, ECU Health’s chief nursing executive. “As a health system serving 1.4 million people, we need more nurses at every level in order to meet the region’s immense needs. The College of Nursing is one of the premiere nursing education schools in the nation and our health system is great training ground for developing a health care workforce with a focus on rural health challenges. I am excited to see the benefit this program will have on our patients and team members.”